Handel's Hercules is something of a conundrum. First performed in 1745, it's technically a secular oratorio and was never intended for the stage, yet it has a dramatic coherence far superior to many works written for the theatre. Dealing with the death and apotheosis of the eponymous strong man, it derives from plays by Sophocles and Seneca, and, unusually for Handel, has something of the relentless force and rhetorical flavour of classical tragedy.

Its early audiences considered it too severe; modern listeners are apt to find it disquieting for different reasons. The protagonist is not Hercules himself, but Dejanira, his suspicious wife who unwittingly destroys him in an attempt to regain his love after accusing him of sexual betrayal. Handel's remorseless examination of the psychology of jealousy has few equals in music drama.

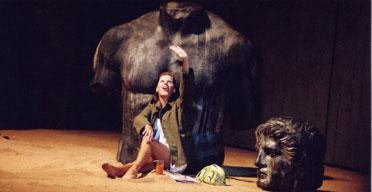

Luc Bondy's production, much hyped on its first appearance at Aix in 2004, is an uneven effort. The drama plays itself out in a sandpit strewn with fragments of erotic statuary and enclosed by concrete walls. There are some awkward uncertainties of tone. Titanic figures and emotions are brought down to earth and domesticated. Hercules is a sleazy military type. Iole, the object of Dejanira's jealousy, has become a ditsy airhead, who peruses the pages of Marie Claire.

Some of the singing is fabulous, though. Joyce DiDonato gives the performance of a lifetime as Dejanira, hurling out coloratura with the fury of a psychopath before descending into insanity. William Shimell's Hercules is all bravado until disaster strikes, after which his physical agony is vividly realised. In the pit, William Christie conducts Les Arts Florissants with intensity. One major problem throughout, however, is dreadful diction, with the words simply inaudible for huge stretches of the evening.

· Ends tomorrow. Box office: 0845 120 7500